There’s a writing concept that I’ve seen people describe in a few different ways. The one I repeat the most, which I learned from my friend Jay Wolf, is, “Yelling so the people in the cheap seats can hear you.” Another, via Bree and Donna of Kit Rocha, is “dropping the anvil.” Yet another, more distant but still related concept, is “writing for the second screen*.”

What do I mean by all these things?

When you’re trying to convey something essential to the reader, you have to make sure they pick up what you put down. If you don’t, they may get confused or upset or disengage from the story.

Everyone reads differently, and it can vary by day or mood or a million little things. Some readers—friend Jay calls them “close readers”—catch subtle hints, innuendos and subtexts and casual references that are mentioned once and never again.

Others—call them “loose readers”—aren’t reading as carefully, for any of many reasons: they’re tired, they’re speed-reading, they keep getting distracted or interrupted, there’s a lag between reading days or times. Still others are skimming, scanning, reading mostly the dialogue, skipping to the saucy bits.

Because everyone is reading your work differently, it’s worth—within reason—finding ways to accommodate those differences as you write, to make sure as many people as possible are getting the essentials.

You yell so the people way in the back of the theater can hear you, not just the ones in the front row. You drop the anvil so the people who didn’t notice your more delicate hints are sure to spot that one. You use techniques that allow the people experiencing your work like it’s a second screen—multitasking, being interrupted, surrounded by noise—to catch what’s important instead of missing it.

A prime example comes from my new book, Witch You Would. Multiple readers have asked the same question: can anyone in this world do magic?

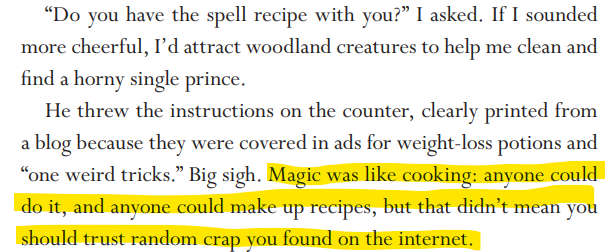

The short answer is: yes! It’s mentioned on page two, quoted in the section below, in which a customer is being nasty:

So if the answer is right there (and in a couple of other places), how did so many people miss it?

Because I didn’t yell it for the cheap seats.

What are some ways to accomplish this? A few ideas:

- Repetition. If you only say a thing once, some people are sure to miss it. If you repeat it a few times, in different ways, each repetition increases the odds that more people will catch it instead of having it whoosh past them.

- Clarity. The more obvious and direct you are about saying a thing, the more likely it will be that people understand it. Don’t only be ambiguous, or subtle, or sneaky: say it loud and proud somehow, somewhere. Drop that anvil.

- Placement. Where you say a thing can make a huge difference in how many people notice and remember it. Dropping vital intel at the end of a paragraph, or in the middle of a complex sentence? Might as well hide it under a rock.

- Pacing. If you say too many important things all at once, readers may only absorb the first one or two. Spread out your revelations and lore drops. If they’re all anvils, you’re going to give someone a concussion.

These techniques can be especially useful—and extra necessary—if you’re deviating from genre standards and expectations somehow. The more people have particular tropes or concepts entrenched in their subconscious, the harder you have to work to make them understand that you’re doing something different.

Take my example above: readers are primed to expect magic to be hereditary, or granted as a gift or curse by some powerful being or artifact, or have some extremely specific rules system you have to learn. That means I have to repeatedly and clearly say how it actually works in my book, or how are readers expected to know?

This doesn’t mean you can’t do subtle, drop hints not everyone will catch, or let readers read between some lines. There’s so much potential for satisfaction in noticing some bit of foreshadowing that pays off later, or rereading and seeing everything you missed the first time. It’s about conveying the things you think they MUST know so that as many readers as possible will get them.

And if you’re writing books for only the most discerning of palates, readers who can taste all those different flavor notes in your complex wine? That’s okay, too! Knowing your target audience for lets you cater to them accordingly. Are you writing for the smoothie drinkers, or the slow food crowd?

Have any other techniques or tips for how to project and pitch heavy objects at reader heads? Share them in the comments, or drop me an email, or tag me on socials if you’re so inclined!

*Longer explanation of the second screen thing: a lot of TV and film writers are being asked to write in a way that ensures people who are treating their TV as a second screen—as in watching something while also staring at their phone, or working on their computer, or doing something else—are still going to get the gist of what’s happening. This is why sometimes you’ll have, say, a character repeat something another one just said, or describe something you can clearly see on the screen.